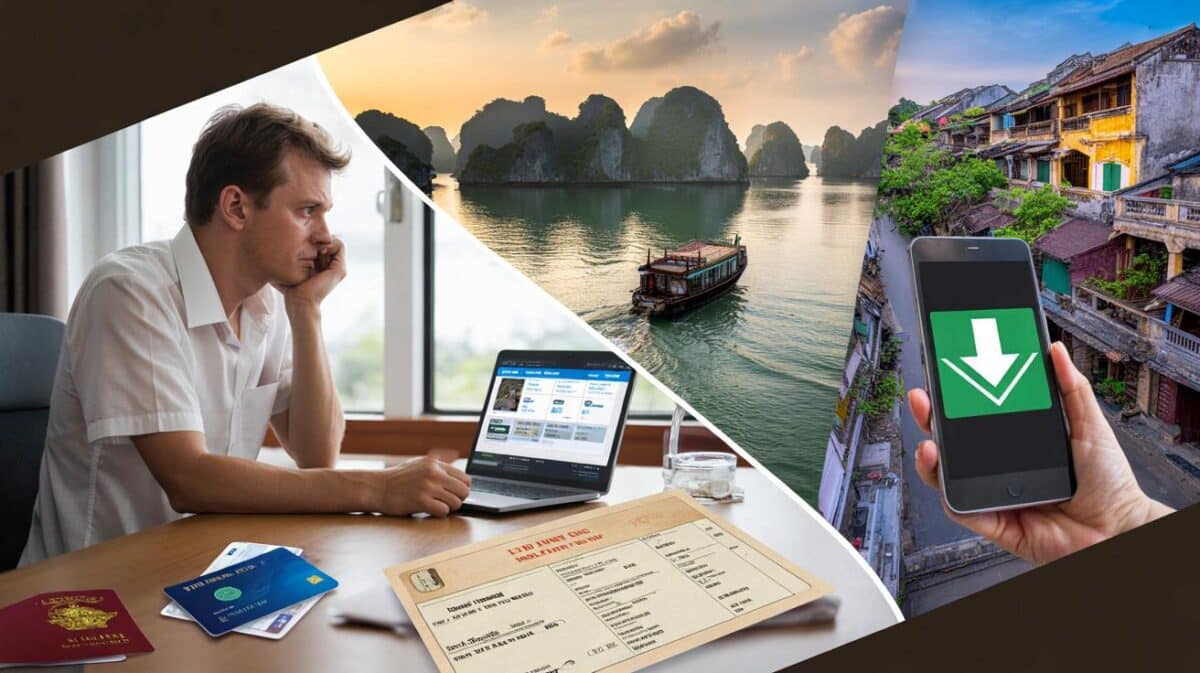

Her move maps onto a wider shift. Around 500,000 UK residents left last year, while 72% of 18–30-year-olds say they would consider working abroad. One British family chose Caraíva, a boat-in village on Brazil’s north-east coast, where life runs on river tides, WhatsApp groups and neighbourly favours rather than buses, sirens and supermarket queues.

Why one British family packed up for Brazil

Caraíva sits on a sandy peninsula in Bahia. There are no paved roads. Carts replace cars. Boats do the heavy lifting. The Pataxó people live nearby and shape daily habits. Outdoor life dominates. Children roam barefoot. Parents talk at the water’s edge.

The family rent a three-bedroom house with a large garden for £460 a month. The plot yields pineapples, herbs and shade. Capuchin monkeys visit the trees. The Atlantic murmurs from beyond the dunes. The beach lies three minutes from the front door.

No cars. No screens. A three-minute walk to the ocean. A £460 monthly rent for a three-bed with a garden.

Childhood here looks analog. The parents limit screen time to almost nothing. Play happens in hammocks and on riverbanks. Evenings run to firelight and chatter. It resembles a slower 1980s Britain, only warmer and saltier.

Schooling gaps and choices ahead

One public school serves the village. It sits 12 minutes from the family home. Term started a month late because the nursery lacked a teacher. Staff sickness is frequent. Low public-sector wages do not help recruitment or reliability.

The children are three and five. The parents accept the patchy provision for now. They may move to a larger town as the children age. Homeschooling remains a discussion point, though Brazilian rules around it are not straightforward and vary in practice.

The nearest hospital is about two and a half hours away in Porto Seguro. Police reach the village by helicopter or canoe.

Work, money and the arithmetic of distance

One parent works remotely as a data analyst for a US public agency. A dollar income stretches far in Bahia. The other is building a local health retreat. Living costs look different when transport is by boat and food arrives from the garden or riverbank.

There is no supermarket in the village. Most food is fresh and local. Neighbours sell homemade shampoo and moisturisers. The family employs a housekeeper for laundry, tidying and lunch. The role costs £300 a month. That sum sits above the local going rate. It frees time for parenting and paid work.

| Item | Caraíva (family’s reported reality) | Typical big-city UK |

|---|---|---|

| Rent (3-bed) | £460 per month | Often £1,700–£2,200 per month in London |

| Domestic help | £300 per month for daily support | Rare; nanny or cleaner costs far higher per hour |

| Groceries | Local produce; no supermarket; more scratch cooking | Supermarket basket; broad choice; higher packaging costs |

| Healthcare access | Free SUS system; limited on-site supplies; long travel | NHS access; variable waits; nearby facilities |

| Commute | None; remote work | Common daily commutes and fares |

Safety, health and the reality of remoteness

Bahia’s postcard beaches share space with a drug-trafficking reputation. The village feels calm day to day. Petty crime is rare. People return lost phones. Yet the area has seen gang disputes away from the tourist zones.

There is no permanent police presence in the village. Residents post alerts in WhatsApp groups and stay indoors until helicopters arrive. The community helps with emergencies. Drivers ferry neighbours to clinics. Herbalists and nutritionists fill small gaps. The public hospital system is free at point of use. Vaccinations happen quickly. Supplies can run short, so people carry basics at home.

Community support is constant. Health services are free. Distance and delays shape every decision in a crisis.

The wider exodus

Half a million people left the UK for new lives abroad last year. Survey data from the British Council suggests 72% of 18–30-year-olds would consider living and working overseas. Motives range from the cost of living to childcare prices, wage stagnation, work-life balance and climate. Some mention romance and social life. Others point to housing costs and rent churn.

The Bahia move touches several of those themes. Rent fell by four figures a month. Childcare stress eased because paid help is accessible. Family time increased. Screens faded. Community ties grew. Risks rose in other places: healthcare access, education choices and the thin blue line of law enforcement.

What this lifestyle asks of you

- Language: Portuguese helps daily life, school meetings and clinic visits.

- Income: a remote salary or secure local plan keeps budgets stable.

- Connectivity: test mobile and fibre options; outages can disrupt work.

- Healthcare: know the nearest hospital and carry a first-aid kit.

- Schooling: confirm start dates, staffing and long-term pathways.

- Legal status: visa rules change; check entry, residence and work permissions.

- Tax: track residency day counts; seek advice on worldwide income and social charges.

- Safety: agree family protocols for late-night travel and local alerts.

- Weather: plan for heavy rain, river levels and coastal storms.

- Community: contribute time or skills; mutual help is the main safety net.

A village without cars, a life without hurry

Daily rhythms centre on the river and sea. Weekends drift toward the water. Parents sit ankle-deep on sandy banks while children play. Short canoe trips reach quieter beaches. When the family stays home, they light a fire in the garden. They talk. They bake. They watch birds in the shade.

Work still happens. Meetings stack across time zones. Bahia runs three hours ahead of New York for much of the year and up to four ahead of the UK in summer. Early starts or late calls come with the territory. Many residents build small businesses geared to visitors. Lodgings, retreats and guided walks keep money local.

Thinking of making a similar move?

Run a three-month simulation before you go. Live on your target budget while in Britain. Remove car costs. Add boat fares and emergency travel. Cook from scratch. Reduce reliance on delivery apps. Track work hours against Brazil’s clock. See what breaks first: money, patience or Wi‑Fi.

Map schooling from nursery to age 16. Visit the nearest town with strong options, such as Itacaré along the Bahia coast. Speak with headteachers. Ask about teacher turnover, exam routes and language support. Confirm transport in heavy rain. Consider a back-up plan if staffing thins mid-term.

Health planning matters in a remote setting. List the exact route to the nearest hospital. Save key numbers. Store basic medical supplies at home. Many families add a low-cost private clinic plan in the nearest city for scans and specialist appointments. Keep tetanus and routine vaccinations current for adults as well as children.

Respect for local communities underpins a gentle life here. The Pataxó culture shapes the area. Buy from local traders. Follow access rules on beaches and paths. Learn names. Share time. Small places remember who helps and who takes.

The exodus from Britain is not one story. This Bahia chapter shows the trade-offs in sharp relief. Lower rents and richer community life sit alongside fragile infrastructure and longer journeys to care. Some readers will see freedom. Others will see risk. The calculus is personal, and the numbers and values are very real.

Idyllic, sure, but a hospital 2.5 hours away and a school term starting a month late are big red flags. In an emergancy at night, who gets you out? And don’t forget visas and double‑tax traps—costed those in?